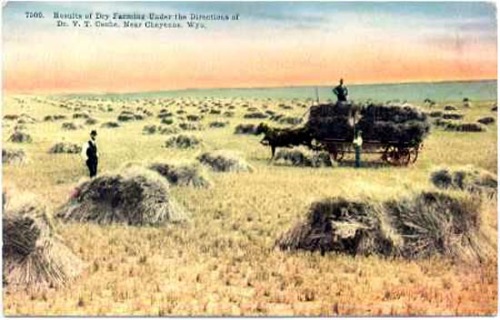

“Results of Dry Farming Under The Direction of Dr. V. T. Cooke, Near Cheyenne, Wyo.,” 1906

“Results of Dry Farming Under The Direction of Dr. V. T. Cooke, Near Cheyenne, Wyo.,” 1906

The great nations of antiquity lived and prospered in arid and semiarid countries. In the more or less rainless regions of China, Mesopotamia, Palestine, Egypt, Mexico, and Peru, the greatest cities and the mightiest peoples flourished in ancient days. Of the great civilizations of history only that of Europe has rooted in a humid climate. As Hilgard has suggested, history teaches that a high civilization goes hand in hand with a soil that thirsts for water. To-day, current events point to the arid and semiarid regions as the chief dependence of our modern civilization.

In view of these facts it may be inferred that dry-farming is an ancient practice. It is improbable that intelligent men and women could live in Mesopotamia, for example, for thousands of years without discovering methods whereby the fertile soils could be made to produce crops in a small degree at least without irrigation. True, the low development of implements for soil culture makes it fairly certain that dry-farming in those days was practiced only with infinite labor and patience; and that the great ancient nations found it much easier to construct great irrigation systems which would make crops certain with a minimum of soil tillage, than so thoroughly to till the soil with imperfect implements as to produce certain yields without irrigation. Thus is explained the fact that the historians of antiquity speak at length of the wonderful irrigation systems, but refer to other forms of agriculture in a most casual manner. While the absence of agricultural machinery makes it very doubtful whether dry-farming was practiced extensively in olden days, yet there can be little doubt of the high antiquity of the practice.

Before complex irrigation systems, farmers still managed to eke out crops even in the worst droughts. As water shortages become more common, today’s farmers are being forced to return to old ways of finding the water hidden in nature.

Yet dry farming is unlikely to win over farmers who still have abundant access to water, fertilizer, and big markets. “Dry farming is not a yield maximization strategy,” says the California Agricultural Water Stewardship Initiative. “Rather it allows nature to dictate the true sustainability of agricultural production in a region.”

Five times the crops with good land management

Improving how we farm drylands could ease food insecurity in some of the areas of the world that are most vulnerable to drought and hunger. Drylands, defined as arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid climates, cover more than one-third of the planet’s land and are home to more than one-third of the population. Without access to information and technology, farms in these lands can falter during yearly dry seasons and suffer catastrophic losses during periodic droughts.

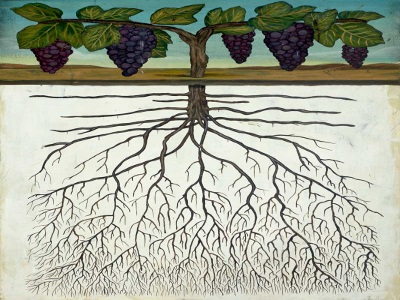

Growing wine grapes without irrigation is less radical than you might think. France, Italy, Germany, and Spain have been dry farming for centuries. The European wine industry doesn’t just frown upon the supplementation of rainfall; it forbids the practice (with a few exceptions; most European countries permit irrigation for newly planted vines, and some have begun loosening regulations in the case of drought). Water mature vines in France, for instance, and you may find your appellation d’origine contrôlée, the industry’s all-important certification of place, revoked. Adding unnatural quantities of water, the thinking goes, means meddling with a wine’s terroir, its unique expression of place. Even in California, grape growers relied on rain alone until the 1970s, when drip irrigation was introduced to the state. The grapes responsible for establishing Napa Valley as a world-class wine region in the middle of that decade—from brands like Stags’ Leap and Chateau Montelena—all came from dry-farmed vineyards.

“Dry farming is a difficult financial niche,” says Little, “but I have found a formula that works for me.” By his own account, it is a formula earned through endless tinkering with both his production methods and his approach to marketing and distribution.

Why dry farm?

When asked what her primary motivating factors for dry farming are , “to build soil, conserve water, and hopefully get consistently more flavorful and nutritionally dense tomatoes.” The presentation affirmed her hope that more flavorful and potentially more nutritionally dense tomatoes can result from some water stress.

” Reasons for dry farming may range from necessity in the case of no water rights or a drought to interest in soil conservation or better tasting tomatoes. If you are interested in exploring dry farming further see the resources below.

What is dry farming?

Dry farming refers to crop production during a dry season, like our summers here in the Willamette Valley, and utilizing the residual moisture in the soil from the rainy season instead of depending on irrigation. Dry farming strategies work to conserve soil moisture during these long dry periods through a combination of management strategies including drought-resistant varieties, timing of planting, tillage, surface protection, and keyline design. Regional rainfall, type of crop, planting depth and spacing, and soil type are important considerations. For example soil quality and water-holding capacity is especially important for dry farming systems and wouldn’t be feasible for most crops on a really well drained sandy soil with little to no organic matter. For each 1% increase in soil organic matter, soil water storage can increase by 16,000 gallons per acre-foot of applied water ! Many people think of grains and beans when dry farming is mentioned, however farmers in the western region of the U.S. have dry farmed many other crops including: grapes, garlic, tomatoes, pumpkins, watermelons, cantaloupes, winter squash, potatoes, hay, olives, and orchard crops .

The strategy for managing soil moisture at Your Hometown Harvests, involves deep straw mulch, low/ no irrigation, and low/no tillage. After trialing this system and great success with tomatoes and winter squash you will decided to expand dry farming onto more acres.

Check evaporation

Plastic mulch on apple sapplings

Plastic mulch covers these apple tree sapplings, locking in the moisture to slow evaporation.

Cover the soil with organic mulch or even plastic sheeting to prevent evaporation. Tilling can also work, turning the surface into a dirt mulch. Groundwater forms films throughout the soil that draw the water upward as the top layer leaches out into the air. Mulch and tillage provide a buffer that slows the water film. Weeding slows the loss of moisture through the weeds’ leaves, a process called transpiration.

Boost water storage

When lands are managed to retain water, leaving fields fallow for a season in dry climates can allow them to soak up enough water to grow crops the next year.

Make good seed choices

Some crops thrive in drier climates. Millet, for example, does much better than corn even in fields that are not properly managed. And, of course, drought-resistant varieties of many kinds of crops are under cultivation and in development now.

Farmers who choose seeds well will be more likely avoid crop losses and they may not need to do as much work to conserve water. The International Crops Research Institute found only marginal improvements on fields that employed good water conservation measures in semi-arid tropical climates when the crops were drought resistant grains and certain grain legumes.

Also, give seeds room to grow. Seeds should be given more space in dry climates to avoid forcing plants to compete for water.

“MY SURVIVAL FARM”

…and it’s like nothing you’ve ever seen before… An A to Z guide on survival gardening that is easy to read and a joy to put into practice, full of photos, diagrams and step by step advice. Even a kid can do this and, in fact, I encourage you to let the little ones handle it, to teach them not just about self-reliance but also about how Mother Nature works.

Here is just a glimpse of what you’ll find inside:

How to plan, design and put into action high-yield survival garden that will literally keep you and your family fed for life, no matter what hits you, even when everyone else around you is starving to death. No digging and planting year after year and no daily watering because you’ll have more important things to worry about when TSHTF.

How to set up highly nutritious soil for your plants. Do this before you plant anything and you’re on your way to setting your food forest on auto-pilot for decades to come. I’m gonna tell you this one “weird” thing to add to the mulch that’s not only highly effective but also 100% free (because you already have it in your home right now).

Step-by-step instructions on how to plant over 125 plants inside your permaculture garden. Plus, special instructions on choosing the right ones for your climate. From Arizona to Alaska, you can do this anywhere…

How to “marry” your plants. We’re gonna tell you which grow well together and help each-other survive and thrive, so they don’t ever compete for sunlight and nutrients. You get the full table of plants that work well with one another as well as the ones you should NEVER be put together. (Source)

Our grandfathers had more knowledge than any of us today and thrived even when modern conveniences were not available. They were able to produce and store their food for long periods of time. The Lost Ways is the most comprehensive book available. All the knowledge our grandfathers had, in one place.Here’s just a glimpse of what you’ll find in the book:

Table Of Contents:

Making Your Own Beverages: Beer to Stronger Stuff

Ginger Beer: Making Soda the Old Fashioned Way

How North American Indians and Early Pioneers Made Pemmican

Wild West Guns for SHTF and a Guide to Rolling Your Own Ammo

How Our Forefathers Built Their Sawmills, Grain Mills,and Stamping Mills

How Our Ancestors Made Herbal Poultice to Heal Their Wounds

What Our Ancestors Were Foraging For? or How to Wildcraft Your Table

How North California Native Americans Built Their Semi-subterranean Roundhouses

Our Ancestors’Guide to Root Cellars

Good Old Fashioned Cooking on an Open Flame

Learning from Our Ancestors How to Preserve Water

Learning from Our Ancestors How to Take Care of Our Hygiene When There Isn’t Anything to Buy

How and Why I Prefer to Make Soap with Modern Ingredients

Temporarily Installing a Wood-Burning Stove during Emergencies

Making Traditional and Survival Bark Bread…….

Trapping in Winter for Beaver and Muskrat Just like Our Forefathers Did

How to Make a Smokehouse and Smoke Fish

Survival Lessons From The Donner Party

Get your paperback copy HERE

Here’s just a glimpse of what you’ll find in The Lost Ways:

From Ruff Simons, an old west history expert and former deputy, you’ll learn the techniques and methods used by the wise sheriffs from the frontiers to defend an entire village despite being outnumbered and outgunned by gangs of robbers and bandits, and how you can use their wisdom to defend your home against looters when you’ll be surrounded.

Native American ERIK BAINBRIDGE – who took part in the reconstruction of the native village of Kule Loklo in California, will show you how Native Americans build the subterranean roundhouse, an underground house that today will serve you as a storm shelter, a perfectly camouflaged hideout, or a bunker. It can easily shelter three to four families, so how will you feel if, when all hell breaks loose, you’ll be able to call all your loved ones and offer them guidance and shelter? Besides that, the subterranean roundhouse makes an awesome root cellar where you can keep all your food and water reserves year-round.

From Shannon Azares you’ll learn how sailors from the XVII century preserved water in their ships for months on end, even years and how you can use this method to preserve clean water for your family cost-free.

Mike Searson – who is a Firearm and Old West history expert – will show you what to do when there is no more ammo to be had, how people who wandered the West managed to hunt eight deer with six bullets, and why their supply of ammo never ran out. Remember the panic buying in the first half of 2013? That was nothing compared to what’s going to precede the collapse.

From Susan Morrow, an ex-science teacher and chemist, you’ll master “The Art of Poultice.” She says, “If you really explore the ingredients from which our forefathers made poultices, you’ll be totally surprised by the similarities with modern medicines.” Well…how would you feel in a crisis to be the only one from the group knowledgeable about this lost skill? When there are no more antibiotics, people will turn to you to save their ill children’s lives.

If you liked our video tutorial on how to make Pemmican, then you’ll love this: I will show you how to make another superfood that our troops were using in the Independence war, and even George Washington ate on several occasions. This food never goes bad. And I’m not talking about honey or vinegar. I’m talking about real food! The awesome part is that you can make this food in just 10 minutes and I’m pretty sure that you already have the ingredients in your house right now.

Really, this is all just a peek.

The Lost Ways is a far–reaching book with chapters ranging from simple things like making tasty bark-bread-like people did when there was no food-to building a traditional backyard smokehouse… and many, many, many more!

Books can be your best pre-collapse investment.

The Lost Ways (Learn the long forgotten secrets that helped our forefathers survive famines,wars,economic crisis and anything else life threw at them)

Survival MD (Best Post Collapse First Aid Survival Guide Ever)

Conquering the coming collapse (Financial advice and preparedness )

Liberty Generator (Build and make your own energy source)

Backyard Liberty (Easy and cheap DIY Aquaponic system to grow your organic and living food bank)

Bullet Proof Home (A Prepper’s Guide in Safeguarding a Home )

Family Self Defense (Best Self Defense Strategies For You And Your Family)

Survive Any Crisis (Best Items To Hoard For A Long Term Crisis)

Survive The End Days (Biggest Cover Up Of Our President)

SOURCE : wyomingtalesandtrails.com

SOURCE : smallfarms.oregonstate.edu | modernfarmer.com