Are you a True BBQ Pitmaster? Do You Know Your Cuts of Pork?

There is nothing on God’s green earth that quite compares to a perfectly-cooked beef steak or grilled or smoked chicken. But my favorite grilled or barbecued animal of choice? It is perhaps the pig.

Pork is undeniably one of the most commonly consumed meats in the world. My preference for swine is due to the meat being sweet and juicy, almost to the point of being deliciously unctuous. I also love pig because there is simply so much you can do with it and types of meat they offer. I mean, you can get ribs, pulled pork, ham, St. Louis-style pork steaks, sausage, bacon…(sigh) What’s not to love?

Where do you start? There are seemingly endless cuts that can be found, some better known than others, even if you only include what’s found at your neighborhood grocery store.

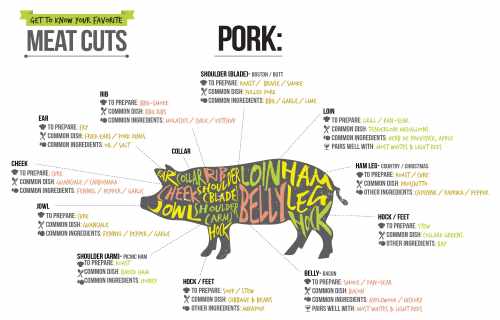

Basically, the leaner and more tender cuts are located at the top of a pig, whereas the lower parts are tougher, fattier, and often require longer cooking times at lower temps to make them juicy and tender.

The cuts below are generally what you find around the United States. Internationally, your mileage may vary when it comes to precise cuts and names.

Picking your pig and preparing your workstations

For home use purposes, you will probably want to select a young gilt (female pig) or a castrated male that weighs from 180 to 250 lbs. A smaller pig is not as economical, and a much larger pig will have a higher percentage of body weight in fat and be less manageable for home slaughter. I have slaughtered animals up to 300 lbs with good results, but the returns from feed do diminish when they get to this stage.

Judging livestock is fairly complex, can take years to learn to do properly, but here are some of the basics you can start with. Look for an animal that is broad in the back, more flat and firm than rounded, as this indicates less waste backfat. If you could balance a tea-tray on the pig’s back without it wobbling, this is a desirable animal. A good wide stance is another hint that there is some solid muscle present; a pig that stands with its hind legs too close together is a less desirable animal.

The shape of the ham, the curve of the buttock and the hind leg, is something else to look at closely. A good, full, round curve means plenty of meat on the animal. A lean, angular, slanted jut to the leg and butt means that the ham is less muscular and lower yielding.

Before slaughter, pigs should be given free access to water but be denied food for at least 12 and preferably 24 hours in order to help purge the digestive system. They should not be crowded, exposed to high temperatures or unnecessarily stressed. Just before slaughter, they can be hosed clean, or scrubbed by hand if they will tolerate handling without becoming stressed. It is not only cruel to stress animals and to cause them unnecessary pain, it results in a poorer meat product.

Humane killing methods, blood collecting and preservation

Tie a secure knot between hock and hoof on one or both of the live pig’s hind legs. On an animal prone to stress, you may wish to tie a noose-type knot and slip it on just one leg as rapidly and quietly as possible. The other end of the rope should already be attached to the pulley or chainfall. Do NOT haul a live, conscious pig up in the air this way. Stun or kill the animal first before hauling it up for the bleeding process.

When you are canning meat products remember these things.

Shoot the pig in the forehead with your rifle at point blank range (one inch away), or use the captive bolt or electrical stunner in the same place. Draw an imaginary “X” between its ears and its eyes, and the center of the X is roughly where its brain is located. DANGER: Do not press the muzzle of a firearm directly against the pig’s forehead, as the gun may jam and backfire.

Assuming the shot was on target, haul the pig into the air immediately to get a good bleed-out, high enough so that its forelegs are barely touching the ground. It will still be twitching due to the cortical disturbance triggering muscle spasm, but it is likely to be dead if a rifle was used, or effectively unconscious if a stunner was used.

If you are saving the blood, and I highly recommend it for use as garden fertilizer even if you are not a fan of blood puddings, place the clean bucket with 1/2 cup of good white vinegar between the pig’s forelegs on the ground – the forelegs should be barely touching the ground. Take care not to cut the windpipe when collecting blood, or you may contaminate the bucket with weasand contents.

Stick the pig. Use a smooth dipping motion to insert the 8 to 10 inch VERY sharp preferably double bladed knife into the correct place on the pig’s chest. At this point, it is advisable to find a picture with a diagram as to where the right place is, because in this instance a picture is worth a thousand words. You are aiming more or less for the heart, but it is the main arteries you will actually be severing.

The motion you are making is like drawing the outlines of a shallow bowl, dipping down and then up again. If you do not get a very copious blood flow immediately, do it again quickly, with the full length of the knife.Allow the pig to finish bleeding out, which can take several minutes. Expect some twitching and continued motion; this will persist whether or not the animal is actually dead. When you have finished bleeding out the pig, you should have 4-5 quarts of blood in your food grade bucket. Add 1/2 cup of non-iodized salt (sea salt is best, or ordinary non iodized table salt) and stir for about 30 seconds. Use a strainer to scoop off and discard the white foam. You now have stable blood that will not clot and will keep in your fridge for weeks in edible form. If you don’t do this, you will have a solid block of blood jello which has much more limited culinary use.Make sure you have at least 4 quarts of blood in that bucket, or your pig is not sufficiently bled out. A good bleed-out involves a very healthy and constant stream of blood, which you can encourage some by keeping the pig’s head slightly lifted so that the fat around the wound does not settle and close it.

Dehairing or skinning, gambrel hanging

Haul the bled-out pig into the tub of hot (150-160 F) water, and use the thermometer and some kettles full of boiling water to make sure it stays that way. You may want to use a long-handled brush to agitate the bristles while the pig is in the hot water. After 5 minutes or so, haul the pig out onto the table and scrape the bristles hard and furiously with your scraping tools – a bell scraper, steel wool and medium-dull knives being good candidates. If the bristles do not come off easily, dip the pig again.

IMPORTANT: Do not allow the temperature to exceed 160F, as you do not wish to cook the pig at this stage, or to set the hairs so that they cannot be scraped loose.

For the final dehairing, use the blowtorch briefly (not enough to blister the skin) and scrape the burned hair off.

If you want to skip the hot water step, you can skin the pig instead. A carcass should be thoroughly chilled before you attempt to skin, or it will be very difficult to handle. Another argument in favor of dehairing versus skinning is that pigskin is a wonderful cooking aid with which to add gelatinous body to soups and stews and to line cassoulet dishes, but before dehairing it is bristly and inedible.

As soon as the dehairing operation is over, dump out the hot water and hose the tub or drum down with cold water – you may be able to use the same large container to bury the pig in ice if you need a fast chill-down because you cannot hang the carcass in a cold room or in cold weather overnight.

Remove the rope from the hock. Carefully pierce the hind hocks behind the large tendon. Insert the gambrel hook, or thread the sturdy dowel through both hocks and tie them to the stick, widely spread apart. You may wish to notch or drill the stick to facilitate this. Attach this arrangement to the pulley or chainfall once again, so that the pig can be hung head-down for the gutting operation.

Preserving edible parts, removing inedible parts, cleaning

Have ready a barrel, large bucket or clean garbage can lined with a big Hefty garbage sack between the pig’s legs, as the word “offal” derives from a very logical etymological source – “fall off” is exactly what the internal organs do when you make that cut.

Carefully “unzip” your pig. Make a tiny cut just below the pizzle or the genital slit, being careful not to puncture any intestines, then slip your hand inside the carcass and keep two cupped fingers on the back of the knife as you cut. This keeps the guts from accidentally being slashed, Unzip the carcass very slowly and let the guts fall down unbroken out of the slit you are making. Guide them with your hands (using gloves is not a bad idea) into the bucket, and be prepared for them to really leap out of that cavity at you.

Warning: macho types who want to gut their kill with a great big Bowie knife will run into real trouble at this stage, as spilling rumen into the abdominal cavity of the carcass can taint and spoil the meat. You want a knife with a 2″ to 3″ blade at most for this step, or your operation will be clumsy at best and unsanitary at worst.

Pigs are the only animal I ever gut with a head-down hang, since the physical structure of the hind hocks are more suitable to take a gambrel stick and the weight of the head and neck are a strong counterbalance. If you don’t mind destroying the front hocks and you want to take the head off first thing, I recommend a head-up hang so that you don’t have the “leaping intestines” problem. On a head-up hang, I begin the incision just below the rib cage, which allows me to better control how the unwieldy mass of the intestines and stomach come out.

You will be removing the innards in three stages: the stomach and intestinal mass in the abdominal cavity, the cluster up in the thoracic cavity behind the thin, tough membrane of the diaphragm that comprises the heart and lungs and a few other attached bits, and the kidneys and fatty bits up near the spine. The intestinal mass will be the most unwieldy and difficult, which is why the head-up hang may be the best one for beginners.

When the intestinal mass appears and begins to bulge out of the carcass, continue unzipping slowly, guiding the mass to fall down into the waiting sack. Don’t forget to carefully remove the caul fat, the lacy white covering over the intestines, as this has some superior uses in cooking.

When the mass is mostly out, you will find that it is still attached to the carcass and other parts by stringy, tough connective tissue. You will have to carefully sever any connections between the digestive system and other organs. Let the stomach fall into the barrel; it’s tough and won’t burst unless you were clumsy with the knife earlier. The rest of the mass will likely remain attached; fish around the diaphragm (just under the heart and lungs) with a short bladed knife that is not too sharp and find the connections to cut when you’re ready to dump the stomach and guts. You may find it helpful to haul out the guts in your fists and try to have the connective tissue visible before you cut into it. Small scissors can also be invaluable at this stage.

You will come to a final length of small intestine that leads out of the body on the hind end. This is the bung. Squeeze it as clean as you can from the outside, then cut it about a foot from where it exits. Tie off both severed ends securely in a knot, and push the knot through and out the other end of the carcass.

Not far from here is the bladder, and this should likewise be removed with great care and discarded into a separate wastes bucket. Don’t let go of the tube on the end of the bladder until you get over the wastes bucket.

Take a small, sharp knife and cut out the pig’s entire rectum, with some flesh around it, including the tied-off bung. Carefully discard this unclean bit, without letting it touch the meat.

Do not allow any unclean material inside the lower intestines or in the bladder to touch the meat; hose off any contamination immediately. When you are done with this part of the operation and have isolated the stomach and guts into one bucket and the rumen, waste and bladder into another bucket, wash your hands in antibacterial solution or bleach water (10% solution) and change gloves before you deal with the large, edible internal organs such as the heart, lungs and liver.

If you plan to use the intestines for sausage casings (hard work but rewarding) or the stomach for Irish style haggis, you may want to begin soaking them in salt water or a light (10%) vinegar solution. The bladder may also be emptied and saved, though it has little culinary use except as a convenient container that was traditionally used for rendered lard. Sterilized glass jars work well for such storage, so the bladder can be discarded in good conscience unless you are a traditionalist or short of jars.

Beyond the thin, tough membrane of the diaphragm, fish around and grab a tough bundle of flesh up past the heart that is attaching the rest of the more solid innards to the carcass. Cut it as high up inside as you can reach, and pull. The whole mess will come down, so have another clean sack ready. This mess, except the green bubble attached to the liver, is good eating – don’t waste it. Wash it well and save it on ice. You can eat the heart, the liver, the lungs, the spleen and the diaphragm, though I recommend throwing the latter scrap of tough flesh into the stock pot with the headcheese. Remove the nasty green gallbladder from the liver carefully and discard it without letting it burst or contaminate the meat.

Fish through and separate the guts for immediate discard, immediate cold storage and short term cold storage for processing within the hour. I discard only the lower intestine, the colon and all stomach contents, and I save the stomach and upper intestines for washing and scraping clean for sausage casings and haggis, leaving them in a bucket that goes in the cold room for processing later.

If you want to process them now, here’s how. Wash the stomach in running water and scrub with a brush. Store it wet, soaked in a 10% vinegar solution in cold water. Cut the intestines into 18″ to 3″ lengths, depending on how long you want the sausage strings. The intestines must be scraped with a slightly blunt edge – the back of a knife, a pastry scraper or a dough scraper.

Squeeze and scrape all the extraneous material out of the intestines until you are left with a translucent paperlike shell. Use more force than you think you need to. Small rips are not a major problem, and even if a length of intestine leaks water, it will often still hold sausage meat adequately.

You may wish to do some additional cleaning by attaching one end to the kitchen faucet and running water through it vigorously. Store the finished, translucent, paperlike tiny scraped intestines slightly damp, buried in noniodized salt.

Wash your hands with soap and water and a 10% bleach solution when you are done with the intestinal mass, then move on to a separate clean butchering area.

Make a moderately deep slit in both the kidneys and the top of the heart, and make sure the liver is clean of the green gallbladder. Remove the spleen (a long, dark colored strip of meat) and the spongy lungs. Place all of these organs in a food grade bucket filled with lightly salted distilled (clean) water and some ice. You want to get all blood clots out of the heart, and open up the kidneys a bit so that some of the disagreeable smell and taste can drain. Some people split the kidneys and soak them in cold milk overnight, which gives good results. Save all of these organs; they are good food.

Take a hose to the inside of the carcass once it is gutted out, or if you are field butchering away from a water source, wipe down with a damp cloth thoroughly. At this stage, it is important to allow the carcass to chill and firm, otherwise the meat will be mushy-textured, hot, slippery and hard to work with. Standard practice is to chill in a cold room or out in cold weather at 32 to 40F overnight, but I have cheated by using an ice tub and burying the carcass under about 40 lbs of ice for a few hours before continuing to work. If you do hang outdoors or in a cold room that is not sealed, you will need to shroud the meat against flies, wrapping it tightly in cheesecloth.

As soon as the meat is no longer soft, soapy and slippery, and has stiffened up a bit – it will do this fastest if hung where it is coldest, or iced down – you can commence you cutting as you wish. I advise doing the primal cuts, then hauling each of those cuts inside where you can fiddle with your books and diagrams and think carefully about how to chop them up, bone them, etc.

Rough diagram for primal muscle cuts:

- Jowl bacon, a valuable cut.

- Neck chops, less tender than the loin but still usable, located at top of shoulder

- Shoulder. The lower section with the legbone is picnic shoulder.

- Loin chops, the most valuable section. The rear loin will have the psoas muscle (tenderloin) included under the backbone.

- Bacon or sowbelly.

- Hams

- Fatback, the solid slab of hard fat across the back of the pig

Your processing area should be very clean and well lit and stocked with many many sharp knives, a hammer and cleaver and some type of meat saw. You can actually use the same table as you did for dehairing, but it’s time to apply the hose and a new clean plastic sheet.

Remove the head by cutting deeply all the way around it and feeling with the point of your knife for the severing point between skull and vertebrae. If you fish around in here long enough to get impatient, you may wish to use the cleaver and hammer technique. Place a large cleaver blade down on the bone, and firmly strike the back of the cleaver with a hammer. Repeat until the bone is split through, and wipe or rinse away any resultant bone chips.

Remove the valuable jowl bacon squares (the cheeks and jowls) and reserve. The remainder of the head can be used for headcheese, and boiled whole or split in half after removing the eyes (some remove eyes and brain). The ears are an especial delicacy, and after being boiled into tenderness, are delicious when dipped in beaten egg and cracker crumbs and broiled with some mustard, French country style.

If you have room in your cold storage, the head will benefit from an overnight stay in the brine crock and can be placed there immediately.

After removing the head for easier handling, the first recommended cut is to split the pig down the backbone. For this cut, I recommend using a reciprocating (mechanical) saw, or a hand-held meat saw. Again, wipe or wash away the resulting bone chips. It is possible to use a cleaver and hammer to go through the backbone, but more difficult given the length of the cut and the difficulty in positioning the cleaver.

Preferably using a photo diagram, separate the shoulder and foreleg from the neck and backbone. Set this section aside for later processing in your kitchen; you can decide whether you want a whole foreleg ham, or several picnic ham and shoulder sections.

You can generally see where the joints are in the legs, and an experienced home butcher can disjoint a carcass by using a small, sharp knife to effectively take it apart at the seams. At least attempt this method, but if it fails you at first, a cleaver and hammer positioned where you think that joint is works well also.

Mark out and remove the side of bacon, slicing it off the ribs in a square that starts behind the foreleg and well under the thick, round loin muscle and goes to just in front of the hindleg. How much meat you leave on the ribs depends on whether you like spare ribs or bacon best. Skin the slab of bacon, and if you have a female pig, carefully trim and remove the mammary seeds that will be located in the flesh above the nipples.

Using a meat saw or reciprocating saw remove the rib bones just below the loin (pork chop) muscle you see attached to the backbone. A cleaver and hammer can be used, but you risk splintering the ribs if you are not already skilled with this technique. Section them as you like for storage or immediate use on the barbecue.

Working carefully with your visual diagram, remove the back leg at the hip, fleshing it away from the pelvis bone. If you plan to skin your ham, or section it into ham steaks, you may wish to skin the hind leg while it is still attached to gain better leverage. Set aside the leg for more processing in your kitchen. If you plan to skin it and trim fat away, don’t put it in the brine crock yet.

The hind hocks (the ones you pierced with a dowel or gambrel stick) are often considered inedible commercially because they have been broached, but for home use, if you have used a clean dowel or gambrel, they should be fine. Separate them at the “ankle” joint and reserve them for use. You may wish to parboil them briefly in order to remove the “hoof cap”, which should pry off fairly easily with a knife or a curved fork. All of the trotters (forelegs) can go in the brine crock immediately.

Take a look at what you have left. Carefully remove the skin in a thin layer, leaving a generous covering of fat – you can trim this as carefully as you like in your kitchen later on, and you probably want the pigskin pretty clean of fat for most culinary uses. Save the pigskin; it freezes nicely, and it makes a beautiful lining for a slow-cooked cassoulet as well as gelatinizing stocks and stews.

Separate the pelvis, and trim off whatever doesn’t look like a nice, neat rack of pork chops. For ease of handling, I recommend cutting what’s left into three sections – the neck chops, the central loin and the back loin. Look carefully at the lay of the muscle; the divisions should be obvious to you. If they are not, refer back to one of the recommended books and photo diagrams that will help you get the job done.

Secondary cutting:

Shoulders, hams, pork chops, ribs, neck, bones

At this stage, you have a lot of large hunks of pork – two foreleg-shoulder chunks, two hindleg-ham chunks, three “pork chop” sections, two slabs each of spareribs and bacon, not to mention some scraps, the head and some internal organs. At least, that’s one possible configuration – if your first attempt does not resemble anything you have ever seen in neat rows in the supermarket, take it philosophically and continue processing. The directions that follow are not particularly dependent on the shapes you cut the meat in.

What you need to know before you start cutting:

** For long term storage (freezing) cut as little as possible and remove as little outer covering (fat and skin) as possible, as it will help preserve the meat. If you plan to roast immediately, only go to the work of skinning if you are health conscious and wish to also remove most of the fat. Crispy pig skin is delicious when scored into a diamond pattern by slashing with a knife and rubbed with salt before roasting.

** Most cuts of pork can be improved by a day in the brine bucket – it firms up the meat considerably, and adds better moisture retention during cooking. Do not salt or even lightly brine any meat you plan to store more than one month in the freezer, as salted fat has a much shorter freezer life. If you have room in cold storage for several large brine buckets, all four legs, the loin cuts (the pork chops) and the head and trotters can benefit, after being trimmed of fat to the desired degree, from an overnight soak in brine. Do not brine any pieces before trimming the fat to the desired degree.

** Pieces meant for brine cure should be skinned and a knitting needle inserted and removed alongside the bone at both ends, several times. Pieces meant for cold cure should be skinned and deboned. Full penetration of brine and cold cure is critical for a healthy and successful preservation. This is not necessary for the overnight brine cure, only for the pieces destined for bacon or ham.

** Begin with many, many sharp knives and have a helper who will continually resharpen them. You will dull knives faster than you think while you are doing this, especially for the first time. Good quality sharp knives will save you an amazing amount of time, cussing and hurt.

** Have ready a lot of heavy duty freezer bags and an indelible marker to record what is in them, or you will be scratching your head at all the mystery bags in the freezer for months to come.

At this point, you’ll have to decide what cuts will be right for you and your household. If you plan to throw some major parties soon, you may leave some of the larger cuts intact (legs, whole loin roast) as an impressive menu item for the feast. If you have limited storage space, you may want to debone and throw most of the shoulders into the cure with the bacon (yes, this does produce an excellent product in the cold cure), make a lot of terrine and sausage, debone the legs into three or four roasts and remove the loin muscles (both on top and underneath the backbone) for easier storage.

Generally, a good and simple plan for the average household goes like this:

Take the unskinned picnic shoulder from the foreleg, separating it by the lay of the muscle from the meat attached to the shoulderblade. You should have a nice, round small ham. This can be left unskinned and frozen or roasted immediately, skinned and cured in brine, or skinned and boned and cured in dry cure.

Remove and trim the neck areas from the shoulder roast; use trim in headcheese, terrine or sausage. The shoulder roast may be separated into two pieces by sawing through the shoulderblade, or you can ask your butcher to bandsaw the shoulder into steaks for immediate use. You can also bone out the meat if storage space is a concern, or slab it into 1 1/4″ thick squares or rectangles for curing along with the bacon. Shoulder meat is ideal sausage and terrine meat, and can also be preserved in rillettes or rillons.

You may bone out the neck and use the meat for headcheese, terrine or sausage. Some people hot-smoke the neckbones, or barbecue them.

Head, hocks and tail: Put them in the pot of boiling water or the brine for headcheese, along with any other random trim that looks gristly. Even if you plan to pickle the feet in vinegar and brine later, they benefit from parboiling.

Hind legs: You have a classic “ham” here, and you may wish to brine cure and smoke these pieces, or dissect into much smaller pieces for pressed dry cure, immediate use or freezing. An excellent cold cure can be achieved on a deboned ham using the same recipe given for bacon, though the cure takes a few days longer for the thicker pieces, and is done when the meat is uniformly firmed up to the touch. Ham definitely benefits from some time in the brine bucket if it’s convenient. If you do not debone the leg, insert a knitting needle down into the meat next to the bone on several sides to help facilitate the brine penetration.

Pork chops: You should have three sections of “chops”, one less desirable section from the neck which is often boned out for sausage meat or headcheese, one middle section and one back loin with a tenderloin “eye”. Cut these sections into manageable parts if you can’t easily store them in these lengths. Slice through the meat neatly with a sharp knife, then use the cleaver and hammer to go through the backbone. If you plan to use them within one month, definitely give them one day in the brine crock to improve their consistency and flavor. Trim the fat covering to your liking before they go into the brine, but don’t leave them naked or they will cook up dry and tough. If storage space is a serious issue, debone the chops and keep only the tenderloin, processing the bones immediately for stock.

Save the bones. They make excellent stock. Roast them in the oven at 350 degrees for half an hour with whole onions, tomatoes and carrots, then boil the lot with some bay leaves, celery, salt and pepper to taste. Pork stock is rich and delicious, and can be used as the base for many soups, stews and bean dishes.

Side pork:Set aside your slabs of bacon for curing.

Internal organs: We’ll get to those in Section VIII. Don’t throw them away.

Fat trim: You may have several slabs of fat and a great deal of fat trim. You can save some of the regular sheets of hard fat for lining terrines or barding (draping a fatty covering) over dry roasts for extra richness. The smaller pieces are good for larding (inserting into dry roasts with a larding needle to simulate the extra tenderness of marbling). Hard fat trim is also desirable for inclusion in sausages, so save some aside.

With the majority of the fat trim, you will be rendering lard. Save enough for the sausage, pate and terrine recipes that appeal to you.

Lard, headcheese, sausage, bacon and ham

Lard Rendering:

There are several different kinds of fat on a pig.

Leaf lard or kidney fat: A thick layer of fat on the inside of the carcass, often completely enveloping the kidneys. This is extremely desirable lard, and should be rendered separately from the coarser grades.

Sowbelly or bacon: This is streaky fat with both hard and soft textured fat mixed in with muscle. It lies along the flanks of the pig, and is generally cured and eaten as bacon.

Fatback or hard fat: This can be salted or cured like bacon for keeping, rendered for good quality lard or used to line terrine pans or to tie around leaner roasts, especially game roasts, to keep them tender. You mostly find fatback (where else) on a pig’s back, in great thick sheets next to the skin.

Soft or soapy fat: This is the trim, the scrapings, the gristly soft stuff in and around the muscle tissue. It isn’t good for much, but you can melt it to make an inferior quality lard. Don’t mix this fat in with any other kind of fat; it is not very good for sausage making either.

Caul fat: This is the lacy membrane surrounding the stomach and intestines. It makes poor lard, but it is very attractive as a covering for pates and terrines, to wrap around meat, or to make French country style gayette sausages.

Identify all the different types of fat you will be removing from the carcass, separate them, and use them appropriately.

Rendering lard is not a difficult task. You can start with soaking the fat in cold water overnight, which helps remove any blood or impurities, or you can cut the impurities out and discard them if you don’t mind a little more waste. Chop or grind the fat coarsely. Place the fat (separating into different pans by type of fat) in a heavy cast iron pan with just enough water to keep it from burning, perhaps a quarter inch. Put the pan on a low, steady heat, stirring very occasionally, until melted. You can also render lard in pans in the oven at about 300 degrees.

Pour off the fat as it melts, and store it in clean, boiled glass jars. You can salt and eat the crackings left over, but don’t let any salt get into your lard, or it will go rancid faster.

Headcheese:

Headcheese is one of the more simple and popular uses for the pig’s head, though there are certainly more complex ones – deboning and stuffing, roasting whole, or deboning cheek and jowl in the classic English “Bath Chap” dish are all methods of utilizing this underappreciated cut that have a long historical backing.

If you have enough room in the brine crock to soak the head and trotters overnight, it does improve the flavor for anything you’re thinking of doing to them, including headcheese. But it’s optional; some people don’t have enough cold storage room for that much pig.

To make headcheese, remove the eyes from the pig’s head and set it in a large pot to slowly boil down for four or five hours in hot water and a generous dollop of white vinegar. If you like, add a handful of herbs to taste (bay leaf, thyme and cracked pepper works well), some onions, carrots and garlic. Add all four cleaned hocks as well, and make sure you have neatly de-hooved them first. You can add any meat scraps that you do not want for terrine or pate or sausage also, especially if they are gristly bits that will benefit from long stewing.

You can add those trotters to the headcheese, or you can do something else with them once they have been boiled into softness. You can pickle them in a mixture of vinegar and brine, or bone them and stuff them and roll them in crispy breadcrumbs. The ears, boiled into tenderness on the outside and crunchy cartilaginousness within, are also worth removing and serving up separately.

Splitting the head in half is optional but helpful; if you do, remove the brains and reserve for another use. By the time you’re done butchering at the end of the day, about 5 hours later, you’ll be ready to collect up all the tasty bits that have fallen off the bone and press them into a nice brick of headcheese.

Continue reducing the liquid in the pot to a well flavored jelly, adding wine, salt, lemon juice, herbs and vinegar to your taste. Chop the meat coarsely into rough dice – sorry, no shortcuts here, as the food processor or grinder will turn your headcheese to mush. Layer the meat as interestingly as you like. I sometimes use a whole tongue in the middle, and some pistachio nuts for crunch. Cover with the reduced liquid and allow to set in the cold room or refrigerator overnight If you’ve reduced the liquid enough to just cover the meat, it will set into an attractive jelly. Slice and serve cold.

Making Sausage – From Scratch:

Wear latex gloves for this next part of the job. If you are a complete wuss and don’t even want to do this with gloves on, throw away the guts and go buy sausage casings. Or don’t, if you plan to make only coarse pork sausage, which freezes very well indeed in bulk.

In an area well away from the clean meat (which should be in your fridge, in a brine crock or in your kitchen sink on a bed of ice right now), empty as much of the rumen as possible out of the stomach and intestines in a garbage bag. Tie off and throw away the garbage bag. Take the garden hose to the mess; wash it as well as you can.

Section the intestines into lengths of roughly 18″ to 2 feet. You can keep them longer if you want, but the scraping gets problematical after awhile. Again, squeeze clean, soak and wash. Use a wooden chopstick to turn the intestine lengths inside out, wash some more. You can also run water directly through the lengths of gut, by stretching them around your kitchen sink faucet.

If you prefer chittlins or prepared pork intestines to sausage casings, by all means reserve some or all at this stage, before scraping.

Laying each intestine section on a sturdy plastic cutting board that you can adequately sterilize afterward, scrape it firmly and repeatedly with a dull knife or blunt edged scraper until it is a translucent casing. Practice makes perfect. Don’t mind the small holes; they happen, and they will not interfere with your sausage making. Discard all of the slimy white material that comes off of the casing; this is the intestine lining.

Do a final salt water wash on the casings, dry them briefly and pack them in salt. They’ll keep for weeks that way, until you are ready to make your sausages.

There are innumerable recipes for sausage, but a good basic one begins with the proportions. Standard proportions are 1 lb lean pork (neck or shoulder) to 1/3 to 1/2 pound fatback or sowbelly, 2 teaspoons of salt and spices to taste. Coarsely grind or run through the food processor on slow or pulse speed, being careful not to reduce the meat to mush. Be sure the meat and hard fat is chilled thoroughly before you begin grinding.

Some recipes double the amount of fat, calling for equal proportions. Since you are making your own product, there is no reason you should not experiment at your leisure and produce leaner sausages if you wish. You should be aware that much of the good taste of pork sausage does depend on fat, so if you wish a lower fat dish, you might want to use those casings to produce chicken or seafood sausages instead. Experiment and see where your tastes are.

To stuff sausage meat into your casings, you can use the extruder on a large pasta machine, buy a special attachment for your food processor, or buy an old fashioned sausage plunger. Follow any standard recipe for sausage, using your own desired proportions of fat and lean and spices, and stuff those casings you so laboriously scraped. Do not stuff them overfull. Twist them to form the sausages on the string, and you can crimp them off as you go, or tie knots and make individual sausages.

The more fat contained in your sausages, the more successfully they will keep in your freezer. Glazing sausages with additional melted lard to protect them in the freezer is also a good idea.

Casings are optional for everything but the softer types of sausage, such as blood sausages. Pork sausage patties or balls freeze very well in Ziplock freezer bags. Crepinettes or gayettes substitute caul fat for casing, with a round ball of sausage wrapped in a square of caul fat which has been soaked in warm water and dried off for pliability.

Another excellent sausage “casing” is the skin from a goose, duck or turkey neck. You can fill this with a mixture of sausage meat, chestnuts, rice or even truffles if you are fortunate enough to possess any, and roast it crisp.

Trim your skinned sides of bacon, removing as much fat as you wish, and taking care to remove any mammary seeds (small, hard granules of tissue) from the tissue over the nipples if you have taken a female pig. Prepare a single flat container (I often use very large plastic storage or shoebox containers) by mixing 1 pound of brown sugar to 1 pound of non-iodized salt (sea salt works well) in it. Add cracked black pepper or other seasonings to taste. Cover the sides of bacon with this mixture thoroughly, rubbing it into the meat on every side. Leave no meat surface untouched. Use more of the mixture if necessary; the proportions are fairly simple.

If you wish to cut up the bacon in smaller squares for easier stacking during the curing process in your fridge, this is fine. I tend to add other cuts of meat to the bacon cure, such as fatty shoulder meat and other tempting looking bits off the pig that I think would do well as cured meat. It’s all fair game if you slab it off into pieces no more than an inch and a quarter thick to take the cure.

Stack the slabs of bacon, making sure there is a generous thick layer of the salt-sugar mixture in between them, under them and on top of them. Cover with plastic wrap and weight down in the refrigerator or in a cold room (no more than 40 degrees F) with heavy bricks.

After 24 hours, drain all liquid from the mixture and add more of the dry cure (1/2 salt, 1/2 sugar, spices to taste). Leave it for another 24 hours, then drain again. This time add liquids – maple syrup is an excellent additive, or you can use apple brandy, or both. Other fun additives (but not all at once): bay leaves, rum, nutmeg, sage, liquid smoke flavor.

Some people recommend using a pinch of saltpeter in this stage of the cure. I don’t. There isn’t a lot of point in going to all this work to do your own curing if you aren’t making a better product than you could find in the store, and a natural home sugar cure far surpasses what you can get with chemicals, in my opinion.

Let the bacon sit until the cure has fully penetrated, generally another day or two. Slice off pieces and test it periodically.

Home sugar cured bacon cannot be fried on high heat; the sugar will caramelize and burn. Fry it slowly on very gentle heat, and the taste sensation will reward you. You can keep successfully cold cured bacon unspoiled for many months in your refrigerator in Ziplock bags with a preserving splash of brandy.

Ham:

The basic recipe is pretty simple. Leave a joint of pork in brine in cold room storage (36F to 40F) for a minimum of three days (for a small, skinned and boned cut) and a maximum of 30 days. You can also use a dry cure after the first day of brining, with the same recipe as for bacon – 1/2 noniodized salt, 1/2 brown sugar, spices to taste. Press it under bricks overnight, and when the liquid runs off, you can drain it (or keep it if you’re thrifty) and add enough maple syrup and apple brandy to cover it up again. The meat is done when slightly firmed to the touch. An overcured ham will be salty and will need long soaking, or several changes of boiling water, or both.

When you’re ready to cook it, parboil the ham for about 10 minutes and taste the water – if unpleasantly salty, discard the water and parboil again. When it stays clean and sweet, add some carrots, onions, celery, bay leaves and pepper and simmer slowly for about 30 minutes per pound.

For the final glaze, crust it with mustard, brown sugar and pineapple juice (or any other recipe that suits you) and bake it at 325 for 20 to 30 minutes, making sure the sugar does not burn.

Basic brine recipes and additional ham curing tips are in Section X. Warning: do not attempt to cold cure any meats outside of your refrigerator unless you really know what you are doing and/or have a cold room or reliably cold weather in your area, from 36 to 40F.

Long term storage:

Curing, cooking, smoking, air drying and freezing

There are several ways to achieve good long term storage of your pork. You can use brining or dry curing with salt, or make rillettes or confit, where pork that has been salted overnight and then wiped clean is slowly cooked in its own fat until almost all of the water in the meat has been replaced by fat and salt. Rillettes can should keep for many months, covered completely with fat, in a cool and dark place.

Rillettes and Rillons (preserved cubes and shredded pork)

For every pound of meat, use half a pound or more of good lard or unrendered fat. Use sowbelly or shoulder for this long-lasting French country delicacy. Cut your rilletes (cubes) into 2-inch dice. Cut your rillons (shredded pork) into thinner ribbons of meat, about an inch long and 1/4 inch wide. You can make either or both, and in the same pan if you like.

Place the meat and fat in a heavy cast iron pan, season with salt and pepper and spices to taste, and cook covered at about 300 degrees for 4 hours. Separate the rillettes (cubes) and brown them more crisply in another pan, uncovered. If you plan to preserve them for some time, cook a great deal of the moisture out of them. If you plan to keep them refrigerated and eat them within a week, you can leave them moist. Make sure all of the meat juices end up evaporated or separated from the fat.

Strain the remaining shreds of meat out from the fat. Using a wooden mallet, or a wide meshed sieve, pound and rub and shred the meat into fibers. A food processor or grinder does not suffice for this task, and it will reduce the tasty fibers to unappetizing mush. Season with spices to taste.

Pack the meat (both rillons and rillettes, together or separately) into sterilized glass jars. Pour the clean melted fat on top of them. Do not allow any liquid (water, meat juices) to enter. If the meat is completely covered with lard to a depth of at least half an inch, it will keep in a cool, dry place for months. Cover the jars with cheesecloth, aluminum foil or standard lids, after the lard has cooled and hardened.

Smoking and dry air curing (prosciutto) are two other techniques that have been used historically for long term preservation. Hot smoking is easier than cold smoking, and both are easier and less risky than dry air curing.

Cold smoking adds additional flavor and some preservation value to meat that has already spent a few days in brine. It is best done with plenty of air flow and a temperature of an even 60F. Unless your technique is very meticulous, there is some risk of contamination, so hot smoking is better recommended to the amateur.

One technique of semi-cold smoking mentioned by Jane Grigson is to keep an intense flow of smoke at a temperature below 90F for an hour at a time, allowing the side of bacon or ham two days to dry and cool in between smokings to cool down between applications of smoke. Two or three such intensive sessions is enough to allow the smoky flavor to permeate. Do not allow the temperature to get above 90F at any time, or you will find your bacon melted and your ham toughened. The first smoking session should last half an hour, and the meat is rubbed with peppercorns, spices, thyme and crumbled bay leaves while still warm.

If you get good results, you could move on to the second stage of curing, where the ham continues to be smoked for a few hours a day and dried and cooled in between, until it loses a full quarter of its weight and turns a deep golden brown. Remember that if the process goes wrong at any time, you risk losing a ham. Do not eat or feed to animals any meat that you think went “off” in the curing process.

For long term storage of a ham that has been sufficiently cured, shroud it with boiled sturdy cloth (canvas or linen) and hang it in a cool, dry, dark place where the temperature range does not go below 32F or above 60F. The ideal storage range for fully smoked hams is 55F to 60F. Humidity is a worse enemy than temperature, as moisture will soon cause your hams to grow mold. Fortunately, most surface molds are harmless and can be cut away without damaging the meat beneath.

Hams can also be stored well wrapped in cloth or paper in boxes packed with a thick bedding of cottonseed hulls, raw oats or grain. Bury the hams in the grains, and check them periodically to make sure they have not become infested with insects.

A good place to start experimenting with hot smoking for long term preservation is with pork neck bones and hocks and other inexpensive cuts. You can also hot smoke for immediate consumption. Experiment, and follow the directions on the smoker that you purchase. A very good stovetop model is made by Cameron.

Here is one recipe for an air-dry cure. Although it is supposed to be eaten raw, please consider that there is always some possibility of contamination in a nonsterile home processing operation, or disease in the animal, and proceed with yourown safety in mind.

Dried sausage, raw cure (traditional recipe)

Basic dried sausage recipe: 1

lb lean pork to 1/2 lb fatback,

2 tsp salt, 1/2 tsp each of pepper, sugar, spices to taste, 1 clove raw garlic,

1/2 tsp saltpeterGrind all ingredients together finely.

Fill some large casings (do not overfill), keeping in mind that this sausage will dry and shrink. Hang at 60F or below, preferably with a fan running and plenty of air circulation. As the sausage shrinks, squeeze it down so that it remains compacted. This is a raw, cured pork product, and you should bear this in mind when you consider the safety of making it at home. It is traditionally sliced and eaten raw, but you may wish to cook it for safety.

When all is said and done, the comforts and safety of modern technology are nice to have around. You will probably want to preserve a significant portion of your meat in the freezer.Freezing:You can freeze pork for a fairly long time, though an average sized household that also entertains guests can completely consume one pig over a matter of not very many months. What I find to be most economical is sharing a butchering with at least one other household, so that I can do them more often and the meat is fresher.Keep sections destined for the freezer as large as possible if you are looking at long term storage. Cut into smaller, convenient portions only what you plan to pull out of the freezer and use inside of a month. You may also consider investing in a saw that can cut meat while it is still frozen, making it more convenient to store meat in larger and longer lived pieces in the freezer.

To help protect against freezer burn, use melted lard or even vegetable shortening as a thick coating around the meat, and wrap that up in several layers of plastic wrap to be followed with heavy freezer plastic. Make sure the lard or shortening is pure and free of salt.

Freeze pork within 8 days of slaughtering.Pork can be stored up to 8 months in the freezer if it is not brined or salted, or 2 to 4 months if it has been brined. Ideally, it should be initially “flash frozen” at a temperature of -10F or below, if you can manage this in a chest freezer or by paying a commercial facility if you have only an upright freezer available.

The recommended ratio for freezing food is no more than 2 lbs per cubic feet of freezer space for the initial freezing, well spaced out. After the meat is solidly frozen, you can set the temperature controls back to 0F.Freezing cured or smoked meats often produces tasteless, mushy or poor results, unless they are first cooked.

A constant fresh food source that can feed a family of four for 5-7 years, 365 days per year… without spending any money on store-bought groceries (and without having to manage a season-sensitive garden)

You’ll also get a year-long stock of healthy food customized to YOUR family’s needs and likes, even delicious treats for kids… so you can stop spending hundreds on toxic cans or MREs (such as MSG-filled instant soups)

And if you’re looking to save even more money, you’ll find a few 10-minute tricks to save over $82/month on cleaning products and cosmetics… you’ll eliminate all dangerous chemicals and get rid of that nasty chlorine smell that invades your entire home for days

… And to make it complete… you’ll be cutting $$$ off your electricity bills with a long-lost food-preserving technique that only the Amish still use in North America… use it and you can make meat, dairy, and eggs last for months without refrigeration!

Books can be your best pre-collapse investment.

Easy Cellar(Info about building and managing your root cellar, plus printable plans. The book on building and using root cellars – The Complete Root Cellar Book.)

The Lost Ways (Learn the long forgotten secrets that helped our forefathers survive famines,wars,economic crisis and anything else life threw at them)

LOST WAYS 2 ( Word of the day: Prepare! And do it the old fashion way, like our fore-fathers did it and succeed long before us, because what lies ahead of us will require all the help we can get. Watch this video and learn the 3 skills that ensured our ancestors survival in hard times of famine and war.)